wright | individualism

2020

The series „wright | individualism“ depicts eight of Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings and joined the list of Unesco World Heritage sites in July 2019. Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), presumably the greatest American architect of the 20th Century, has also had great influence on European architecture. He is one of the most important ambassadors of Organic Architecture, a style which originates in the 18th century and was adapted by different architects in the 20th century, each of them developing their own interpretation of it according to their ideological orientation. Just like other vanguard movements, Organic Architecture is part of Classical Modernism, which is said to have lasted from roughly 1920 to 1968. Among the key features of this style was the harmony between a building and its surroundings as well as the use of natural building materials, both of which are particularly meaningful in Wright’s architecture. The close relationship between structure and nature marks most of his designs: “an individual language of form for each place.”

About 400 of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 500 buildings still exist today. Adding 8 of Wright’s buildings to the UNESCO list of World Heritage attempts not only to conserve these, but also his other remaining buildings, which have fallen partly into disrepair.

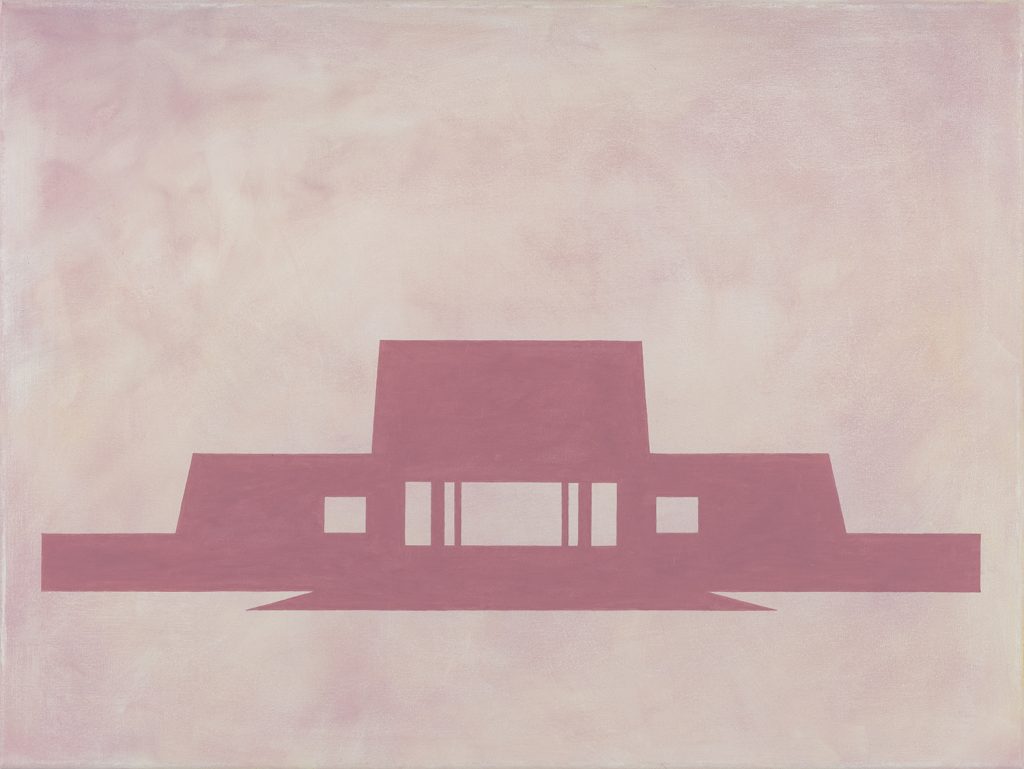

The Unity Temple was built between 1905 and 1909, in Oak Park, a posh suburb of Chicago where Wright himself used to live and work. After the old Unitarian church had fallen victim to the flames, the community approached Wright’s mother, a loyal member, to suggest that her son should design the new building. The Unity Temple is considered the first modern sacral building in America, which is due to Wright’s use of concrete and reinforced concrete, materials that were mainly used for industrial architecture at the time. It was not only Wright’s revolutionary mind that made him choose these materials, but also the fact they were cheap and the financial resources for the project very limited.

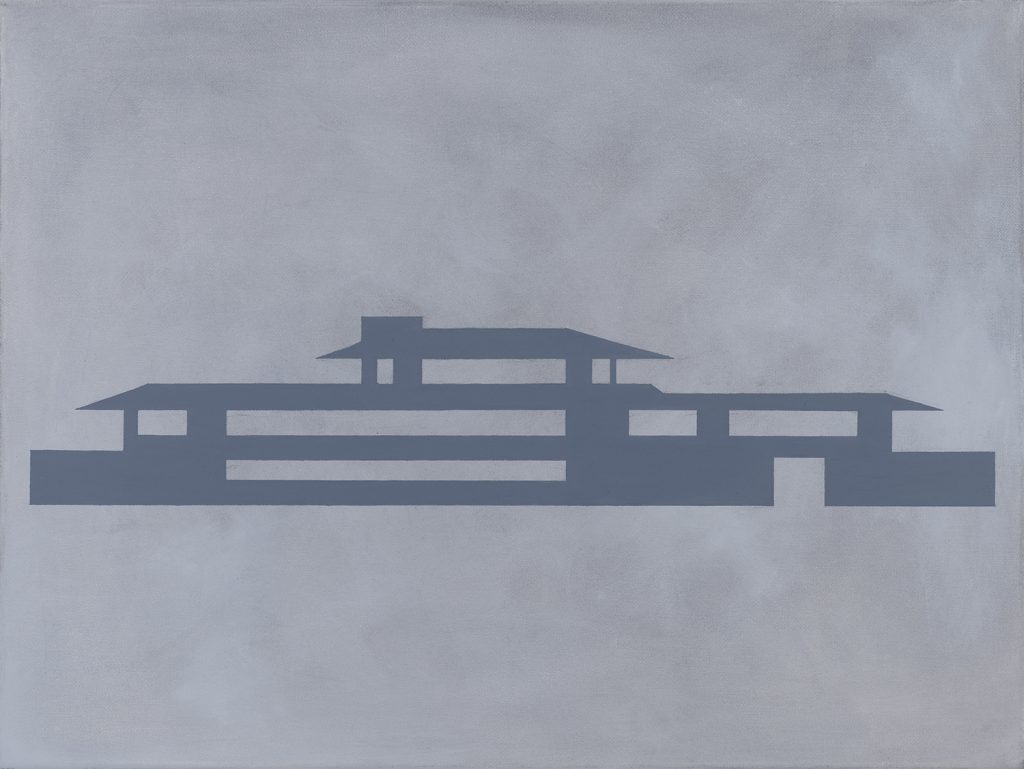

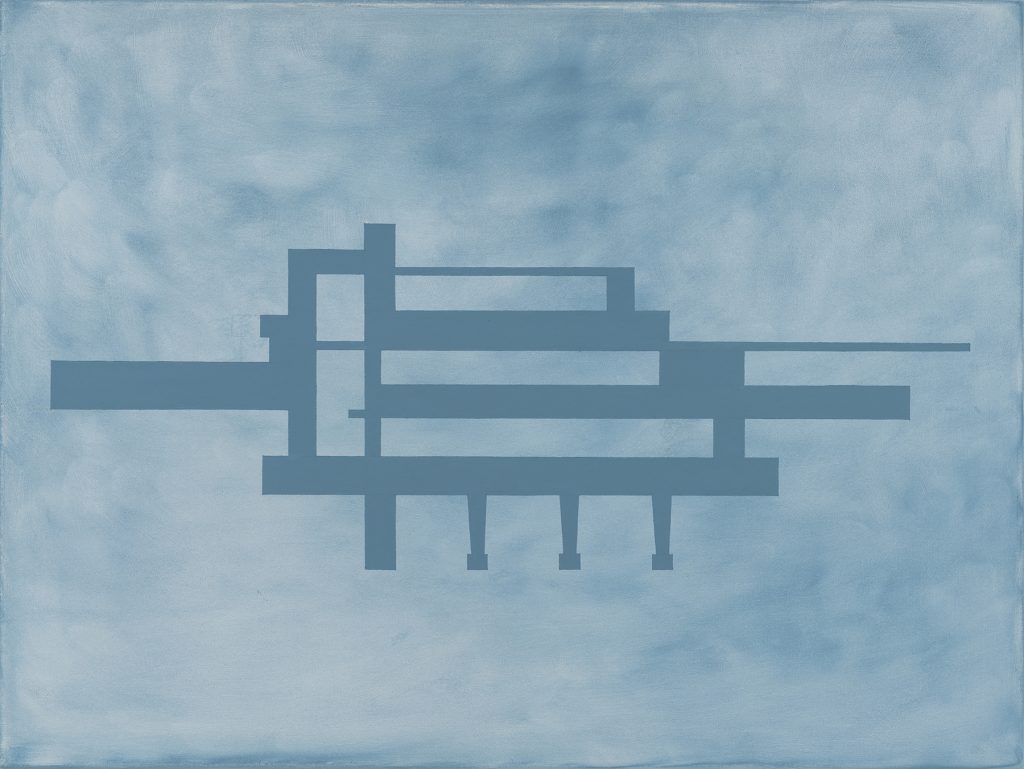

The Frederick C. Robie House was built near Chicago University in 1909/1910. Of nearly 100 Prairie houses that Wright built, this is probably the most famous one. By designing the Prairie houses, Wright and some other architects attempted to create a style of architecture that was characteristically American, which would counteract the predominant neoclassicism. A common feature of all the designs is an emphasis of the horizontal, which should evoke the vastness of the prairie, the primordial landscape of America. Another characteristic in these two-storey houses was the fireplace which was meant to be a gathering place for the families. Another hallmark was the “flowing” merging rooms, which all opened up into the garden, reminiscent of Japanese houses. Wright had developed an interest in Japanese culture in his youth, and had been collecting Japanese art since 1905. At times his art dealing practice was even more profitable than his architectural practice.

Wright also designed the interiors and the furniture for his houses; for the Frederick C. Robie house he came up with the Robie chair, which is still being manufactured and sold today.

Taliesin or Taliesin East was built in a rural part of Wisconsin in 1911, which Wright knew from his childhood. The property, which is situated on a hill, was named after the Welsh poet Taliesin who lived in the 6th century, in appreciation of Wright’s Welch ancestors. It consists of his personal rooms, his studio, and a small school of architecture, which still exists today. Over the course of the years, the property has undergone many changes. In 1914 it was destroyed by a fire, set by one of the employees after he had murdered seven other residents, including Wrights then mistress and her children. Wright re-built the estate. In 1925 it was destroyed by another fire, which was caused by a technical error and followed by another reconstruction, Taliesin III, which still stands today. Wright kept carrying out structural alterations until he died; 200 have been documented. An unbelievable 524 windows in the main building bring the inhabitant closer to the surrounding landscape.

The planning process for Hollyhock House, in Los Angeles, began in 1919. It is the second of ten buildings which Wright designed and built in California. The employer was Aline Barnsdall, an oil heiress and early feminist, whose fondness for hollyhocks determined the style of the building. Hollyhock House was originally planned as part of a bigger complex for art and theatre and as the residence for herself and her artist friends. But as construction progressed her enthusiasm started to wane, partly due to the fact that Wright spent most of his time in Japan, where he was building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. She fired him in 1921, the year of completion. Two Austrian Architects, Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler, who were both strongly influenced by Wright, filled in for him, but in the end the project was completed by Wright’s son Lloyd. For Wright, Hollyhock House meant a diversion from Prairie style and it was when he started using decor in his designs. The motif of a stylised Hollyhock cannot only be seen in the concrete tiles on the facade but also in the windows and the furniture (e.g. on the backs of the chairs). Hollyhock House resembles the Unity Temple from 1909: it has a similar geometrical-square shape, it is closed towards the outside, and there was a similar amount of concrete used. The angular walls of the house also bring Mayan temples to mind. The house itself is made from clay bricks and wood incased from the inside. Clay bricks proved to be a problematic building material, which meant that, over the years, Hollyhock House had to be renovated numerous times.

Hollyhock House is often compared to Ennis House, which is just a few kilometers away. The latter was the scene of a few famous movies and shows, such as Blade Runner or Twin Peaks. Hollyhock House only once served as a backdrop – for the B-movie Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death.

The Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin, completed in 1937, has an entirely different character. One of Wright’s aqaintances, the journalist Herbert Jacobs, asked him to buy a house for 5,000 US dollars. Wright designed a one-storey, 140 sq m, L-shaped residential building, with a big living room and two bedrooms. It was built from bricks and equipped with many glass doors, which offered a great view of the surrounding landscape.

It is the first of Wright’s so-called Usonian Houses, of which he built about 50. In three books, the first published in 1932, the last in 1958, he created the utopia of Usonia, a liberal-democratic America with a federal system and without large, overcrowded cities. In the ideal, decentralised, and suburban Broadacre City – named after the square measurement – each family would have a property of that size, with an affordable 90-140 sq m house to live in self-sufficiently.

Both the Prairie houses and the Usonian houses are explicitly democratic building projects, but the foundation of these designs is also Wright’s Organic Architecture. Wright defined all of his organic constructions as democratic, the luxurious villas, the churches, and other public buildings. This is due to Wright’s understanding of democracy. He despised conformity and was dreaming of a world in which people are given space for their personalities to unfold freely – within an architecture which supports this process: “Organic Architecture is the free architecture of the ideal democracy.”

Wright was also inspired by the famous slogan, coined by his former boss Sullivan: “form follows function.” He extended this demand, saying that architecture should not only follow its function, but also the individual needs of its inhabitants. “For each individual and individual style.”

Over the years, he developed an ever growing artistic freedom, which manifests itself in his increasingly unconventional and imaginative designs. The last three buildings on the UNESCO world heritage list present an impressive example of this.

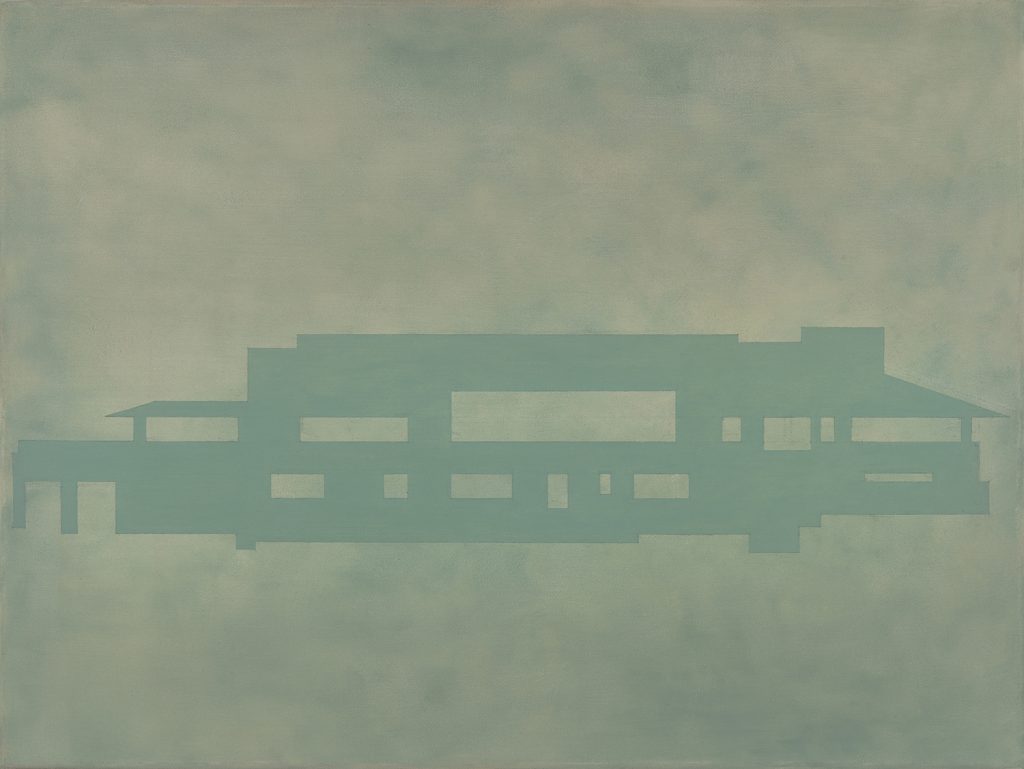

Eventually, winters in Taliesin got too cold for Wright and so, in 1937, he acquired a piece of land in Arizona, close to Phoenix, to build accommodation for this cold time of the year: Taliesin West. The flat, spacious estate, which is perfectly incorporated into the dusty desert landscape, was built in 1938. Wright preferred local building materials, not only for architectural-philosophical reasons but also, as with the concrete, for financial reasons. This is particularly evident in Taliesin West. The rocks, which can be found in the surrounding landscape, were also integrated into the walls, the wood of the native redwood trees dominates the flat, partly asymmetrical buildings which, altogether, look a bit like a residential native American tent camp. Just like Taliesin East, Taliesin West also consists of personal rooms as well as an architectural studio, in which students are still being taught today. The students of the private School of Architecture, which is run by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, study here from November until March and then spend the rest of the year in Wisconsin.

Probably the most renowned residential building in the world, Fallingwater, formerly Kaufmann House, located in the remote forests in southwestern Pennsylvania. It appeared on Time Magazine’s cover page immediately after its completion. It was opened to the public in 1964, and since then, more than 4 million people have braved the long car journey to visit the spectacular building. Fallingwater was commissioned by the cultured American businessman Edgar J. Kaufmann, who wished for a weekend and holiday home with a view over Bear Run river’s waterfall. As is known, Wright was able to persuade him to build the house directly over the waterfall. Like most of his buildings, Fallingwater follows the principles of Organic Architecture: once again, Wright used local building materials, notably stones. They form the solid core of Fallingwater, they serve as a floor covering and they frame the fireplace. Apart from that, Wright repeatedly combined this with large windows, offering panoramic views and prominent horizontal elements, which create a connection between the building itself and its surroundings, this time in the shape of large patios. While they shape the character of the house, they also cause structural difficulties, as they lack the necessary steel reinforcement, which led to countless repairs. Altogether, the renovation works on Fallingwater amount to more than a million US-dollars each year. As with many of his other buildings, Wright also designed the interiors.

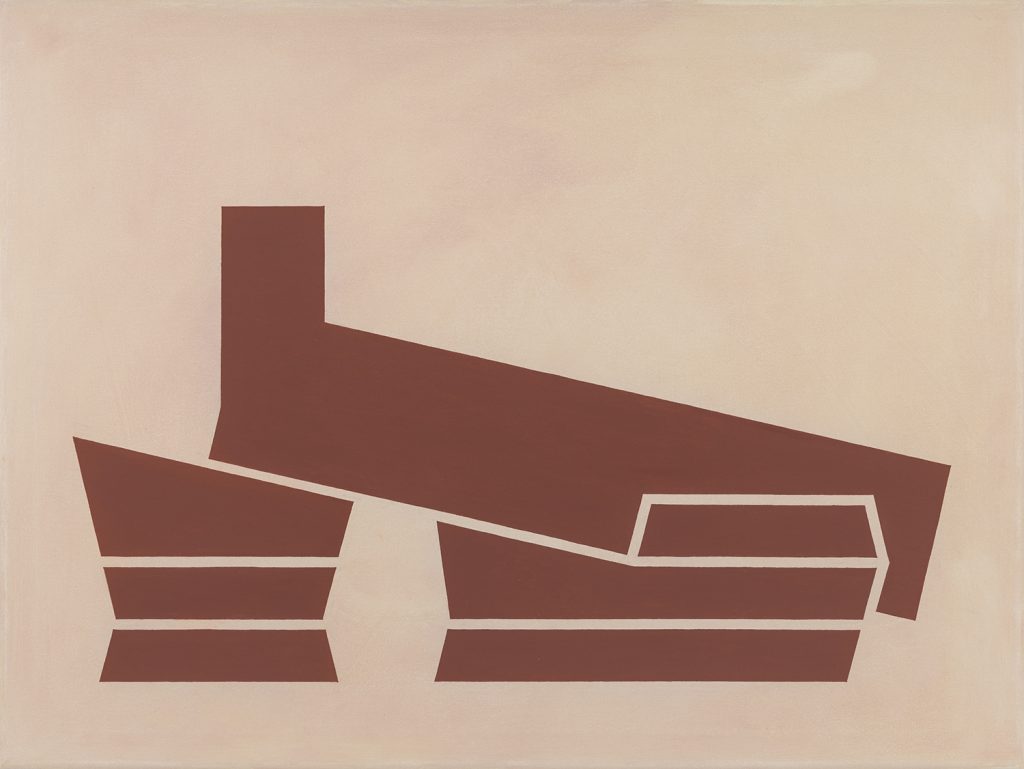

The Salomon R. Guggenheim Museum, or simply the Guggenheim Museum, is one of the last buildings designed by Wright and probably his most famous. When it opened on 21st October 1959, Wright had died six months before, aged 92, as well as the owner, Solomon R. Guggenheim, an American businessman and art collector. The project had been initiated seventeen years before, but quarrels with the building authorities and inflation had delayed the process. There were also disagreements about the shape of the building. Wright prepared 700 sketches before reaching the final shape.

This museum was the first of now three Guggenheim Museums. It stands on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, close to Central Park. The main building is a rotunda, meaning the building has a circular floor plan. The six storeys are connected through a spiralled ramp with a 3° slope. The concrete rings which surround the ramp on each level are wider on the upper floors, which creates the distinctive shape of a truncated cone. All levels open up to the atrium at the center of the building which is roofed by a glass dome. Visitors are supposed to take the lift upstairs and then walk down the ramp.

Wright had already had ideas for a spiral or snail-shaped building in the 1920s, but it was only now that he was able to realise them. Apart from that, the Guggenheim project gave him the opportunity to perfect his idea of Organic Architecture. Until then Organic Architecture, to him, meant creating a connection between a building and nature, whereas now, the building itself almost became natural. This museum stands for itself and can be seen as individualism’s victory over the conformity of big cities, which the architect so despised.

The Guggenheim Museum has been the subject of much discussion and criticism. Wright was accused of arrogance and megalomania, but what needs to be acknowledged is his courage and his unprecedented ingenuity. Even today, this New York building is still fascinating and it practically heralded an era of spectacular museum buildings all over the world.

What often goes unnoticed is the fact that Wright’s personality, as well as his work, was deeply influenced by his religiousness. As mentioned previously, Wright came from a family of Unitarians; his ancestors were actively practising their faith, which rejects the trinity of father, son, and holy spirit. Unitarianism stems from the Protestant Reformation: a religious movement spread from Germany to America, where it flourished in the 19th century. There is a long list of famous followers. Five presidents of the United States were Unitarians, just like writers Charles Dickens and Hermann Melville, chemist Linus Pauling and Florence Nightingale; Albert Schweitzer was an honorary member, and even Thomas Mann, who lived in the United States for a long time, sympathized with the movement.

With its values of liberty, democracy, and individualism, Unitarianism had a major influence on the beginnings of American modernism. It was complemented by Transcendentalism, a reform movement within Unitarianism. By establishing Transcendentalism, its founder Ralph Waldo Emerson created the first original philosophical school in American culture, which has notably shaped literature and politics. Transcendentalism demanded a shift away from institutionalised religion toward individualised religion. Essential for this shift were the renunciation of the bible as well as an orientation towards nature as the manifestation of the divine. In short, one was supposed to connect their inner divinity of the spirit with the outer divinity of nature and thus become part of the all-embracing unity that is God.

It becomes clear that Wright’s strong connection to nature wasn’t only rooted in his rural upbringing, but also in his family’s religious beliefs. After all, he stayed true to them for all of his life. They are not only reflected in the numerous churches he’s designed, but in all his buildings. He was more than an architect, he was an artist who was always aspiring to express himself more truthfully.

Elena Raulf’s architectural paintings are always aimed at the spiritual quality of each of the buildings. She manages to capture it by unhinging the buildings from their scenic, cultural, and historical context, and elevating them to a timeless level. The spectator’s view is directed at the building itself, its peculiarity, its essence. Nothing drowns out the atmosphere it creates by its existence. The same goes for her series of Frank Lloyd Wright’s eight buildings, which were added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage.

Elena Raulf has also taken into account the basic principle of Organic Architecture by incorporating elements from each building’s surroundings. This was accomplished mainly through her choice of colour. The environment is reduced to a diffusely structured, monochromatic background, which is contrasted by the stylized facade of the building. Both are usually shown in different gradations of the same colour.

The choice of colour was often influenced by the building’s setting: blue like the waterfall that Fallingwater was built over, or auburn like Taliesin West’s redwoods.

In psychology, the house is regarded as a symbol of the self. Bearing this idea in mind while looking at Elena Raulf’s paintings and at Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings discloses a deeper understanding of these artworks. They are about more than architecture and aesthetic pleasure. They are representations, images, and sculptures of the self which possess unmistakable individuality, but are also part of an all-encompassing unity.